About the Author(s)

Momina Naveed is a passionate advocate and writer who graduated from the prestigious Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Women’s University, Peshawar. As a dedicated social commentator, she channels her writing to illuminate pressing societal issues, particularly focusing on amplifying the voices of marginalized and vulnerable communities.

Since September 2024, reports have been widely circulated about Pakistan’s economic revitalization. While it’s true that the country no longer faces an immediate financial emergency and has achieved some stability, what about the middle and lower classes—particularly salaried and pensioned individuals– who descended into poverty due to taxes and soaring energy prices over the past few years? Would they be able to regain their status? Isn’t it the government’s responsibility to help them stabilize, too? Now it’s the government’s turn to repay the money taken from them through income tax, sales tax, and exorbitant energy bills.

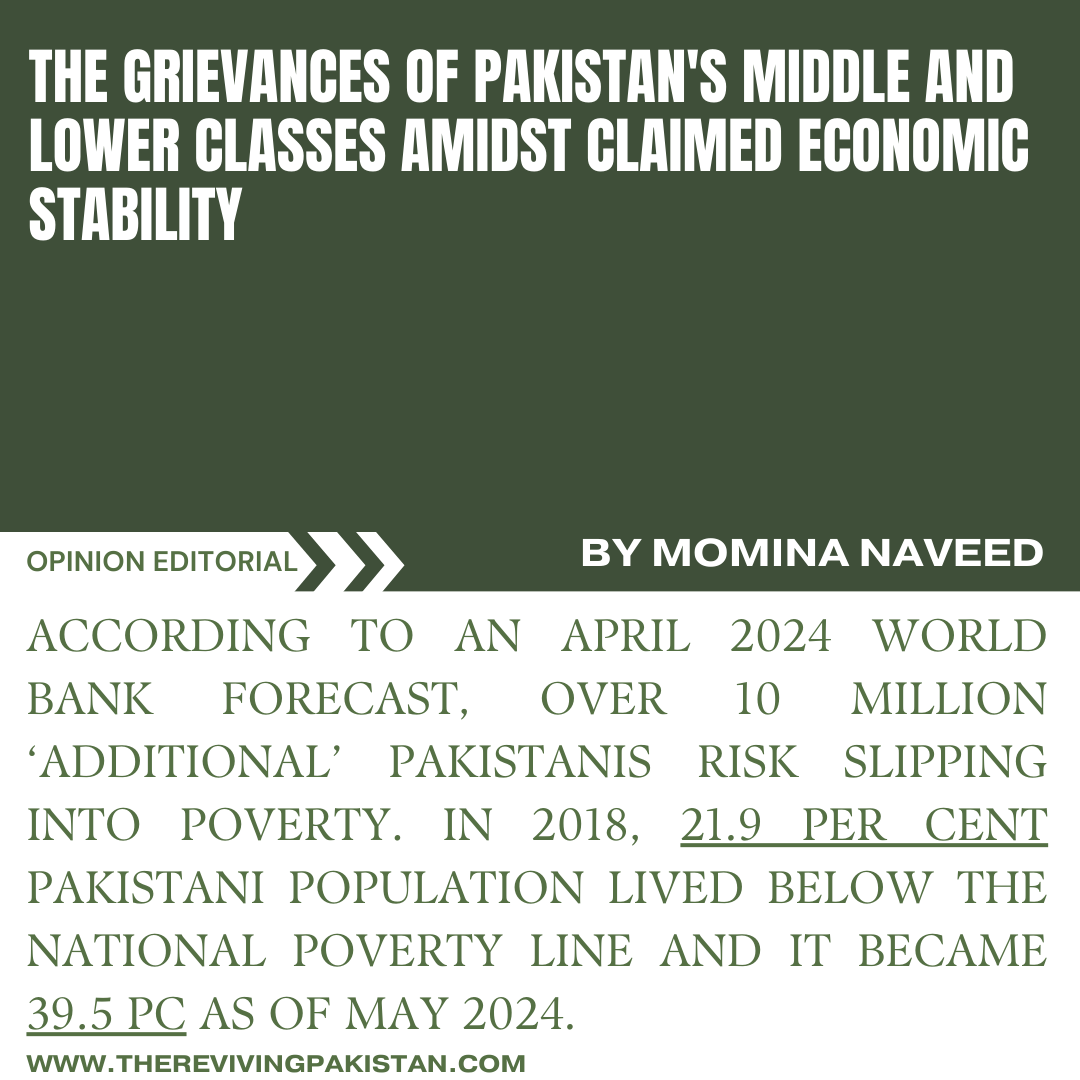

According to an April 2024 World Bank forecast, over 10 million ‘additional’ Pakistanis risk slipping into poverty. In 2018, 21.9 percent of the Pakistani population lived below the national poverty line, and it became 39.5 percent as of May 2024. This surge in poverty is often attributed to population growth, the 2022 floods, and the 2021-22 COVID-19 pandemic. However, the rigorous tax impositions, high energy prices, and inflation also played a significant role.

What was the fault of the middle and lower classes when COVID-19 ravaged the globe, when the 2022 floods hit northern Pakistan, when Russia attacked Ukraine when political instability reached a high peak in Pakistan, and when Pakistan sought an IMF bailout that they had to pay the heavy price by all – financial, physical and psychological – means due to the inability of the government to manage the crises.

The fiscal budget for 2024-25 and the recent IMF bailout – which always comes with conditions – only added to their woes. Shahid Iqbal, an analyst studying the impacts of the current budget, summarized the situation succinctly:

“While the people are still trying to gauge the real impact of the new budget on their lives, an interaction with the man on the street revealed that 40 percent of Pakistanis living below the poverty line had a feeling the government had left them to fend for themselves.”

Currently, the poor are grappling with a range of socio-economic problems, from health crises and malnutrition to declining living standards. Those who once enjoyed modest but comfortable lives now face emotional distress as they witness their financial resources depleting.

Both younger and older generations are feeling the strain. Older individuals, especially parents and grandparents, are overwhelmed with stress, often believing they can no longer meet their children’s demands. With 60-70% of their income swallowed by taxes and bills, what remains barely covers essentials like medical care, education, and basic food.

Meanwhile, the younger generation is burdened by rising unemployment, an inability to seek opportunities abroad, and failure to secure government jobs. For many, this sense of helplessness has led to severe emotional and psychological damage, leaving them feeling like failures for not being able to support their families.

While Pakistan has achieved some economic milestones recently, the government must also support those left behind. And by support, I do not mean financial support such as social safety programs like the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP).

Although such programs have proved valuable for households with no means of earning, many who have “recently become poor” will refuse such aid out of dignity and self-respect.

Instead, the government should provide them with opportunities to let them earn and achieve something on their own. With its independent and motivated spirit, Pakistan’s younger population from such groups only needs a small set of opportunities and support to stabilize their lives—and even exceed their previous economic standing.

The government can help them flourish by giving opportunities such as ease of doing business by providing funds with low interest rates and reforms in educational scholarships, as most of them are based on the annual calculated income without considering the annual tax burden on such incomes (more the income, more the tax); merit-based quota system for such individuals in government posts, and improving their digital skills by providing free courses and work from home opportunities.

In a nutshell, along with improving the country’s economy, the government should improve the economic conditions of those who paid taxes and energy bills to help revitalize the economy. Uplifting this segment will benefit them and drive broader economic growth. A stable and empowered lower-middle class can reduce inflation, fuel industrial growth, and ensure long-term prosperity. Now it’s time to focus on the middle, lower middle, and poor classes of Pakistan rather than the higher and elite classes. Inclusivity rather than exclusivity is the key.