Table of Contents

About the Author(s)

Anoush Khan

The author is a student of International Relations in her 7th semester at DHA-Suffa University. She has a deep passion for writing about pressing global issues.

“In exploring potential mediation strategies to address the Hazara Genocide.”

Abstract

Domestic ethnic conflicts have proven to be very difficult to resolve, however, recent years have shown with global changes, the change in world opinion regarding human rights and democracy. The Hazara genocide orchestrated by Amir Abdur Rahman Khan serves as a poignant example of the atrocities faced by this community, with a devastating 62 percent of Hazara population being decimated. Despite efforts to mediate peace, the conflict has persisted, indicating the failure of these mediation endeavors to bring about lasting resolution. This is an appropriate time since mediation is most effective in preventing a resurgence of violence. This study tries to analyze the potential mediation strategies that can be employed to address the Hazara Genocide. It is crucial to take into account the historical background and ongoing initiatives when investigating potential mediation solutions to address the Hazara Genocide. In this context, memorialization of the Hazara genocide emerges as a crucial aspect of reconciliation and healing. By leveraging historical insights, existing initiatives, creative strategies, and community engagement, mediation efforts can be adapted to address the complex challenges stemming from the Hazara Genocide and advance the cause of justice and lasting peace.

KeyWords: Hazara genocide Peace Ethnic conflict Mediation

Introduction

The present study gestures at the historical account of the atrocities held upon the Hazara, a Shia minority. This paper explores the escalation of violence and the harrowing reality of massacres such as those in Mazar i Sharif, alongside an examination of international responses—or the alarming lack thereof—to these human rights violations. The Hazara people, constituting a significant part of Afghanistan’s ethnic tapestry, have endured relentless persecution over centuries, including slavery, systematic expulsion, and massacres despite once making up nearly 67% of the country’s demographic now dwindled to about 9%1. In present-day Afghanistan, these systemic atrocities persist, morphing into targeted killings, violence, and discrimination primarily fueled by their ethnic and religious identity, underlining a grave human rights crisis akin to an Afghanistan genocide. The Hazaras in Afghanistan, unfortunately, have been subjected to derogatory epithets, being marginalized as “rubes” or outsiders, and in the worst cases, dehumanized as “animals. This tireless assault of Hazaras, amplifies the underlying prejudice, similarly mentioned in The Kite Runner where the Hazaras are categorized as “the mice eating, flat nosed, load carrying donkeys” (Hosseini, p.25) which highlights the critical need for consideration to this marginalized communities’ plight, particularly under the Taliban’s resurgence and their chronicled aversion towards Hazaras in Afghanistan.

Through this paper, the intent is to shed light on the dire situation faced by the Hazaras, advocating for global awareness and action against the backdrop of Afghanistan’s ongoing ethnic strife and power transmission line that further marginalizes this community. This study tries to analyze the potential mediation strategies that can be employed to address the Hazara Genocide.

Research Questions:

1. What is the grass-root resentment of the Pashtun against the Hazara?

2. What are the implications of the Hazara genocide?

3. What can be the mediating efforts towards this ethnic conflict?

Literature Review:

The Hazara people originate from the Hazārajāt region, a rugged, mountainous area in central Afghanistan. They are also found as a significant minority group in Pakistan mainly residing in Quetta and in Mashhad, Iran. It is said that the name “Hazāra ” (هزاره) derives from the Persian word (Hazār هزار) meaning “thousand”. It may be the translation of the Mongolic word (mingghan) a military unit of 1,000 soldiers at the time of Genghis Khan.2 3They are an ethno-linguistic group known for speaking Hazaragi, a dialect of Persian that incorporates elements of Mongolian and Turkic languages. According to historian Lutfi Temirkhanov, the

Mongolian detachments left in Afghanistan by Genghis Khan, or his successors became the starting layer, the basis of the Hazara ethnogenesis.4 Some sources claim that Hazaras comprise about 20 to 30 percent of the total population of Afghanistan.5 They were by far the largest ethnic group in the past, in 1883-1893 (The Uprisings of Hazara) over sixty percent of them were massacred with some being displaced and meanwhile, they also lost a large part of their territory to non-Hazaras that could double their land size today.6

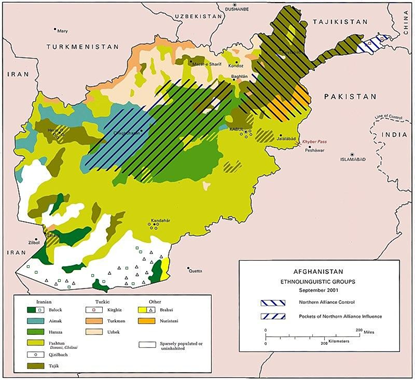

7

Image: Ethnic Groups in Afghanistan

Historically, the Hazaras have faced social, economic, and political marginalization. The reference to the stratification of Hazara society into classes defined by land ownership and production means likely stems from the historical socioeconomic structure prevalent in the region. They have also faced discrimination due to their Turko-Mongol heritage and distinct features, which have led to the propagation of shallow, racist stereotypes. Additionally, an ugly Taliban saying about Afghanistan’s non-Pashtun ethnic groups went: “Tajiks to Tajikistan, Uzbeks to Uzbekistan, and Hazaras to goristan,” with “goristan” being the Pashto word for “cemetery”8. This reflects the dehumanization and marginalization of the Hazara community within Afghan society.

Most Hazaras adhere to the Twelver sect of Shi`a Islam, although there are also communities of Sunni and Ismaili Muslims among them. The historical factors contributing to their persecution also include speculation, prejudices, and arbitrary interpretations of their Shi’a orientation by nineteenth and twentieth century orientalists and scholars.9

Historical Persecution and Genocide:

Genocide refers to the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group. The term “genocide” was first coined by Raphael Lemkin in 1944 combining the Greek word (genos, “race, people”) with the Latin suffix (“act of killing””)10 which was later incorporated into the United Nations Genocide Convention of 1948. The convention defines genocide as acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. One of the most well-known examples of genocide is the Holocaust, the systematic extermination of six million Jews perpetrated by the Nazi regime during World War II constitutes one of the darkest chapters in human history.11

For more than a century, the Hazara community has suffered targeted discrimination, persecution, and genocide based on ethnicity and religious affiliation. Hazara are easily identified by their Asian facial features by the Pashtun. Hazaras experienced genetic admixture with local or neighboring populations and formed the current East-West Eurasian admixed genetic profile after their separation from the Mongolians.12 Their distinguishable features are unable to hide their ethnicity which makes it easier to exploit them for their aggressors. In the 1890s, 60 percent of the Hazara population was massacred in genocidal campaigns, and the survivors were stripped of their land, forced from their homes, and sold into slavery. They were denied access to education and political rights, and oppression continued throughout the 20th century where Afghanistan’s Hazara region remains the poorest region in the country.

Literature on the Conflict between he Hazaras and the Pashtun:

Amir Abdur Rahman, the “Iron Amir” of Afghanistan from 1880 to 1901, is known for ordering the series of massacres and forced displacements against the Hazaras of Afghanistan. His policies, known as the Hazara genocide, aimed to suppress the Hazaras and solidify Pashtun dominance in Afghanistan. One of the most infamous orders attributed to Amir Abdur Rahman is the “Misaq-i-Milli,” or the “Iron Covenant,” in 1891. This decree targeted them and resulted in the massacre and displacement of thousands of Hazara men, women, and children. The Iron Amir’s policies led to widespread atrocities, including forced labor, mass killings, and the destruction of Hazara villages. Syed Askar Mousavi a contemporary Hazara writer, claimed that half the population of Hazarajat were killed or fled to neighboring regions of Baluchistan in British India and Khorasan, Iran.13 These actions resulted in a significant reduction of their

population and left a lasting impact on the community. The oppression and persecution faced by the Hazaras under Amir Abdur Rahman’s rule have contributed to enduring ethnic tensions in Afghanistan.

Following the suppression, the Hazara were terrified and struggled to hide identities, sought to establish defensive positions in areas where their community was concentrated to protect themselves from attacks and to assert their influence in the ongoing conflict. The Hazara armed groups took positions in Kabul’s Shia-majority areas during the Afghan Civil War primarily as a response to the escalating conflict and political instability in the country.14

Burhanuddin Rabbani, president of the time in response to the positions taken by Hazara groups launched an offensive against them in 1993. This offensive resulted in intense shelling, arbitrary killings of civilians, and the targeting of Hazara men, leading to hundreds being killed and forcibly disappeared.15 The actions of Rabbani’s forces, including the killing of unarmed civilians and the devastation of areas inhabited by Hazaras, were reported by Amnesty International.16

When the Taliban, a Sunni Islamist fundamentalist group, occupied Afghanistan in 1998 and captured the northern Afghan city of Mazar-i-Sharif, an uprising against ethnic Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Hazaras broke out. The rise of the Taliban intensified the persecution of the Hazaras. Their extremist interpretation of Sunni Islam led to the targeting of the ethnic minority based on their religious identity, contributing to widespread human rights abuses and atrocities against the community. The Taliban labeled the Hazaras, as “infidels,” justifying persecution and violence against them. 17

However, the Taliban or any other Pashtun ruler have more to the reasoning of the oppression. They dig up to the historical battle of Parwaan, fought between the Hazaras and the Pashtuns in 1221. The Battle of Parwaan was a significant military engagement during the Mongol invasion of the Khwarizmi Empire. During this battle, the Mongol forces, led by Genghis Khan’s generals, clashed with the Khwarizmi army near the city of Parwaan (present-day Bagram, Afghanistan). The Khwarizmi Empire was ruled by Sultan Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu, a Muslim Pashtun ruler. As it is claimed that the Hazara are the descendants of the Mongols, the hatred from the Pashtuns is evident to this day.

According to Bellew (1880)

“Mongol soldiers were planted here (central Afghanistan) as military colonists in detachments of a thousand fighting men by Genghis Khan in the first quarter of the thirteenth century. It is said that Genghis Khan left ten such detachments here, nine of them in the Hazara of Kabul, and the tenth in the Hazara of Pakli to the east of the Indus.”18

The Hazaras themselves claim to be descendants of Mongolians. Today, many Hazara tribal and family names have been adopted by Mongol leaders and commanders.19 The Battle was a major battle, fought for three days and finally defeated on the third day. Since then, this historic conflict between Hazaras and Pashtuns has evolved in different ways. Hence, the Pashtuns view the Hazaras not as Afghans, but as colonists who arrived and settled in the 12th century. The reflection of this hatred between these two ethnic races can be observed in the famous book: The Kite Runner.

“Afghanistan is the land of Pashtuns. It always has been, always will be. We are the true Afghans, the pure Afghans, not this Flat Nose here. His people pollute our homeland, our watan. They dirty our blood. He made a sweeping, grandiose gesture with his hands. Afghanistan for Pashtuns, I say. That’s my vision.” 20

Referring to the quote above, Pashtuns have never embraced them and regard them as outsiders.

Findings:

The Taliban’s resurgence in Afghanistan has markedly exacerbated the plight of the Hazara community. With the establishment of the Taliban’s caretaker government in September 2021, there has been a stark absence of Hazara representation in any significant political or civic roles. Notably, Hazaras are excluded from the 33-member cabinet, and they do not hold positions as provincial or district governors, mayors, or police chiefs.21

The threat to Hazaras has escalated under the current Taliban regime, here has been a disturbing continuation of violent attacks specifically targeting the Hazara population. In the region of Dasht-e-Barchi alone, at least half a dozen targeted attacks have been recorded. Furthermore, mass casualty events have occurred in Shiite and Hazara houses of worship in Kunduz and Kandahar, resulting in over 90 fatalities and hundreds of injuries22. This pattern of violence is not new; historically, Hazaras have been subjected to systematic attacks, including the significant massacres in Mazar-e-Sharif in 1998 and Afshar in 1993.

The Discussion:

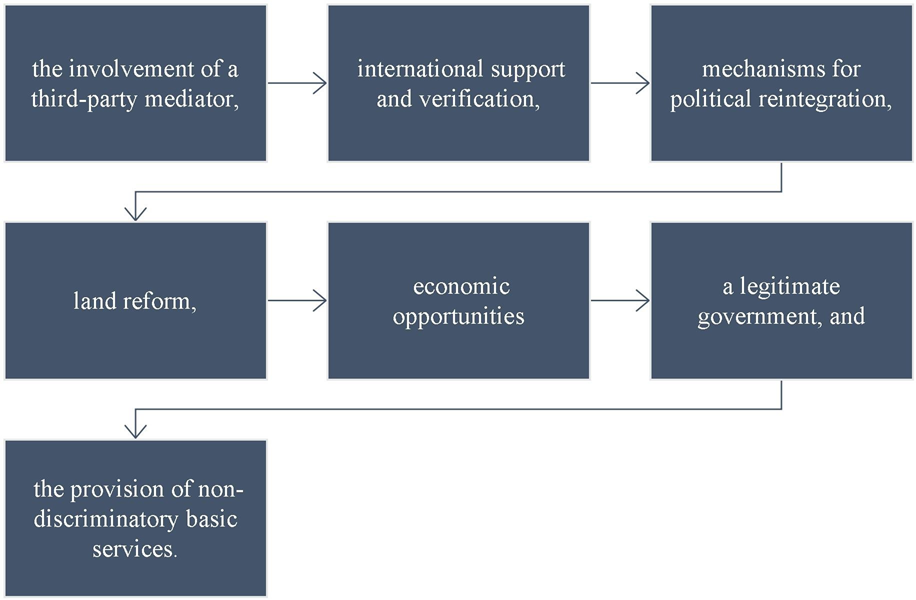

The main purpose of this paper is to ponder upon the mediation efforts that can be employed to address and resolve such heinous massacres against ethnic communities within the international system. The peace process in El Salvador (1992) offers valuable insights for mediating conflicts in Afghanistan. Key elements for success include the involvement of a third-party mediator, international support and verification, mechanisms for political reintegration, land reform, economic opportunities, a legitimate government, and the provision of non-discriminatory basic services.23

Mediation Strategies for the conflict resolution of Hazara Genocide:

It is vital for states like the U.S. and other international entities i.e. the United Nations to engage directly with the Hazara community to provide emergency humanitarian assistance and protection to those at risk of atrocities and displacement in Afghanistan.24 However, international mediation, while a potential avenue for reconciliation, faces numerous challenges. It is primarily a state-centric activity that often lacks sensitivity to the unique conditions of ethnic conflicts which can lead to interventions that reinforce the status quo rather than addressing the root causes of conflict. This can be perceived as a threat to national sovereignty, leading states to resist external involvement. The international system’s tendency to maintain the status quo can

result in mediators reinforcing existing power structures, which may not be conducive to genuine conflict resolution.25

Significant ethnic conflict resolution efforts that have garnered global attention and from which lessons can be learned for communities like the Hazara is one from South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Following the end of apartheid, this commission was formed to help heal the nation and bring about a reconciliation of its people by uncovering the truth about past human rights abuses. Apartheid was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. 26

Apartheid was characterised by an authoritarian political culture based on ”baasskap” (lit. ‘boss-ship’ ), which ensured that South Africa was dominated politically, socially, and economically by the nation’s minority white population.27 In this minoritation system, there was social stratification, where white citizens had the highest status, followed by Indians and Coloureds , then Black Africans.28

The central purpose of the Commission was to promote reconciliation and forgiveness among perpetrators and victims of apartheid by the full disclosure of truth.29 The commission heard testimonies from thousands of victims and perpetrators, documenting atrocities committed during the apartheid era. These testimonies helped to uncover the truth about the human rights violations that occurred. Perpetrators of crimes under apartheid could apply for amnesty if they confessed their crimes fully and truthfully. However, not all perpetrators received amnesty, and some cases were prosecuted in court. The TRC recommended reparations for victims of human rights abuses. While the TRC played a significant role in bringing some closure to victims and their families, reconciliation in South Africa remains an ongoing process, as the wounds of apartheid run deep.30

Similarly, like the TRC establishing a dedicated commission focused on truth-telling and reconciliation could provide a platform for both Hazara and Pashtuns to share their experiences and grievances openly. This could help in building empathy and understanding between the communities. Encouraging both communities to share their perspectives and experiences openly can help in acknowledging past wrongs and building a shared understanding of historical grievances. The commission could explore mechanisms for providing amnesty to individuals who are willing to confess their involvement in past atrocities, provided they offer genuine remorse and commit to contributing positively to reconciliation efforts. It is also essential to ensure that those who have committed serious crimes are held accountable through appropriate legal processes.

However, reconciliation is a complex and ongoing process that requires sustained efforts beyond the work of a commission. Community dialogues, cultural exchanges, education initiatives promoting tolerance and understanding, and economic development projects aimed at reducing inequalities can all contribute to long-term reconciliation between the Hazara and Pashtuns.

Supporting local and international NGOs that work to protect and empower minority communities can be an effective mediation strategy. Locals connect with one another naturally. International actors must tend to support human rights actors, local actors, and organizations through funding, cybersecurity training, and other tools to enhance their capability to protect and advocate for the rights of their ethnic communities. Promoting education and awareness programs that focus on tolerance, diversity, and the history and culture of minority communities can also foster understanding and reduce conflicts among them.

Humanitarian assistance should mainly aim to provide aid including food, medical care, shelter, and education, ensuring that aid is distributed without discrimination. Aiding members of minority communities who are forced to flee their homes, whether internally displaced or seeking refuge in other countries, is also very important for their secure immigration and asylum.

Conclusion:

The persistent challenges and atrocities faced by the Hazara community in Afghanistan spotlight a critical intersection of ethnic, religious, and political strife, underscoring a dire need for international attention and action. Throughout the narrative, we’ve delved into the historical persecution of the Hazaras, their current plight under Taliban rule, and the complex dynamics of ethnic conflict within Afghanistan’s borders. This exploration not only reaffirms the gravity of the situation but also calls for a concerted effort toward safeguarding human rights and fostering peace and security for this beleaguered minority. It is imperative that global interventions and support mechanisms are strategically mobilized to protect the Hazaras against continued oppression and genocide.

The journey towards achieving peace and securing protection for the Hazara community hinges on amplifying their political representation, enhancing legal and security frameworks, and ensuring the provision of humanitarian assistance devoid of discrimination. By advocating for these pathways, the international community can make a significant impact on the lives of the Hazaras and contribute to the broader goal of equity and justice in Afghanistan. Let this analysis serve not only as a reflection on the Hazaras past and present struggles but also as a beacon of hope for a future where ethnic and religious diversity is celebrated, and all Afghans can coexist peacefully.

Bibliography:

- https://minorityrights.org/communities/hazaras/

- Schumann, H. F. (1962). The Mon-gols of Afghanistan: An Ethnography of the Moghôls and Related Peoples of Afghanistan. La Haye. p. 115

- Poladi, Hassan (1989). The Hazâras. Stockton. p. 22.

- Temirkhanov L. (1968). “О некоторых спорных вопросах этнической истории хазарейского народа”. Советская этнография. 1. P. 86.

- Khazeni, Arash; Monsutti, Alessandro; Kieffer, Charles M. (December 15, 2003). “HAZĀRA”. Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- 978-9936-8015-0-9. ISBN .انتشارات امیری :کابل .تاریخ باستانی هزارهها (2013).عباس , 6.

- http://www.army.mil/cmh/brochures/Afghanistan/Operation%20Enduring%20Freedom.htm

- https://thediplomat.com/2021/05/school-attacks-on-afghanistans-hazaras-are-only-the-beginning/

- Baiza, Y., 2014. The Hazaras of Afghanistan and their Shi‘a Orientation: An Analytical Historical Survey. Journal of Shi’a Islamic Studies, 7, pp. 151 – 171. https://doi.org/10.1353/ISL.2014.0013.

- Lemkin 2008, p. 79

- https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-holocaust.

- He, G., Adnan, A., Rakha, A., Yeh, H., Wang, M., Zou, X., Guo, J., Rehman, M., Fawad, A., Chen, P., & Wang, C., 2019. A comprehensive exploration of the genetic legacy and forensic features of Afghanistan and Pakistan Mongolian-descent Hazara.. Forensic science international. Genetics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2019.06.018.

- Alessandro Monsutti (December 15, 2003). “HAZĀRA ii. HISTORY”. Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved December 16, 2012

- https://euaa.europa.eu/country-guidance-afghanistan-2023/3142-individuals-hazara-ethnicity- and-other-shias

- https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/10/27/why-the-hazara-people-fear-genocide-in-afg hanistan

- https://minorityrights.org/communities/hazaras

- Bellew,p. 114).

- (Hosseini, p. 40)

- https://extremism.gwu.edu/risks-facing-hazaras-in-taliban-ruled-afghanistan

- https://extremism.gwu.edu/risks-facing-hazaras-in-taliban-ruled-afghanistan

- https://www.csis.org/analysis/lessons-el-salvador-peace-process-afghanistan

- https://www.ushmm.org/genocide-prevention/blog/urgent-action-needed-hazaras-in-afghanist an-under-attack

- https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/conf/rio01/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apartheid

- Mayne, Alan (1999). From Politics Past to Politics Future: An Integrated Analysis of Current and Emergent Paradigms. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. p. 52

- Mayne, Alan (1999). From Politics Past to Politics Future: An Integrated Analysis of Current and Emergent Paradigms. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. p. 52